An empirical analysis of 80,000 annual observations of listed companies highlights the predominant role of accumulated financial resilience in predicting defaults, closely followed by business cycle effects and macro-sectoral exposure.

Accumulated resilience, cyclical positioning, and macro-sectoral factors dominate the explanation of default risk over most operational financial indicators.

Introduction: Explainability – An Essential Requirement for Credit and Investment Decisions

In M&A, private equity, and corporate finance transactions, the ability to anticipate a target company’s default risk directly determines decision quality. Traditional credit analysis relies on standardized financial ratios (leverage, interest coverage, liquidity), supplemented by qualitative assessment of industry and macroeconomic context.

Machine learning now enables quantification of these intuitions and objective prioritization of risk drivers. However, in a heavily regulated environment (ECB/EBA guidelines on internal risk models) and with multiple stakeholders (boards, investment committees, regulators), explainability is non-negotiable: a “black box” model is neither auditable nor practically usable.

This study applies explainable machine learning techniques to a large dataset of 80,000 annual firm observations to identify the true determinants of corporate default risk.

Methodology: Dataset, Models, and Evaluation Metrics

Dataset Scope

The dataset comprises 80,000 firm-year observations of companies listed on Nasdaq and NYSE from 2000 to 2018. Each observation includes:

Over 20 financial indicators: long-term debt, EBITDA, EBIT, net sales, gross margin, total assets, accounts receivable, equity, operating cash flow, retained earnings, etc.

Detailed sectoral classifications: division (macro-sector), major group (micro-sector), enabling fine-grained industry exposure analysis.

Target variable: default status (binary), with a strong class imbalance typical of real credit data (defaults < 5% of observations).

Models Employed

Several model families were tested and compared:

Clustering (K-Means, DBSCAN) to identify homogeneous risk profiles and uncover latent data structure.

Random Forest, a robust ensemble method handling complex variable interactions and providing native feature importance measures.

LightGBM, a gradient boosting algorithm optimized for large datasets and strong performance on imbalanced classes via weighting techniques.

Neural networks (multilayer perceptron) to capture subtle non-linear relationships and assess added value of more complex models.

SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) to address class imbalance by synthetically generating minority (default) observations, avoiding bias toward the majority class.

Evaluation Metrics: AUC and Precision-Recall

In highly imbalanced settings, overall accuracy is misleading. A naive model always predicting “no default” would achieve 95% accuracy if defaults represent only 5% of cases, yet be completely useless.

Two metrics were prioritized:

AUC-ROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve): measures the model’s ability to discriminate between healthy and risky firms regardless of decision threshold. AUC ≥ 0.85 indicates strong discriminative power.

Precision-Recall Curve: focuses on effective default detection. Precision measures true positives among all alerts; recall measures the proportion of actual defaults caught. In M&A screening, missing a default (false negative) is far more costly than a false alert (false positive).

Explainability via SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations)

SHAP, grounded in game theory, assigns each feature a marginal contribution to the prediction for every individual observation. It decomposes model outputs transparently, showing which factors increase or decrease risk and by how much.

This transparency addresses three critical requirements:

Regulatory compliance: ECB/EBA guidelines mandate that internal credit risk models be validatable and interpretable.

Decision-maker trust: boards and investment committees need to understand why a target is deemed risky, beyond a mere probability score.

Actionability: identifying concrete levers for risk mitigation (financial restructuring, sectoral diversification, cycle timing).

Empirical Results: Hierarchy of Risk Drivers

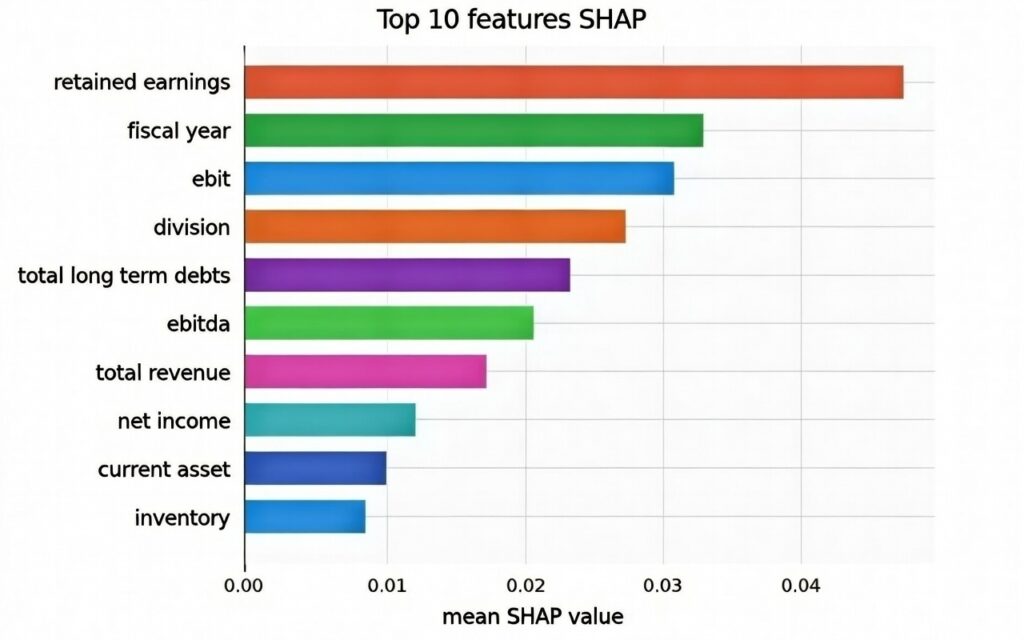

SHAP analysis, aggregated across the full dataset and derived from the best-performing model (Random Forest, AUC = 0.86), reveals the following ranking of the top ten default risk drivers (ordered by mean absolute SHAP value):

1. Accumulated retained earnings

2. Fiscal year

3. EBIT

4. Macro-sector classification

5. Total long-term debt

6. EBITDA

7. Net sales

8. Net income

9. Current assets

10. Inventories

Interpretation: Accumulated Resilience, Business Cycle, and Macro-Sector Before Most Financial Indicators

This finding challenges conventional credit analysis practices that prioritize operational ratios (leverage, profitability, liquidity). The data show a different reality: accumulated financial resilience (retained earnings), cyclical positioning (fyear), and macro-sector exposure (division) are the primary drivers of default risk, ahead of most intrinsic financial health indicators.

1. Retained Earnings: Key Indicator of Accumulated Financial Resilience

In this dataset, where negative retained earnings are absent or extremely rare, this metric emerges as the most powerful explanatory factor. It serves as a robust proxy for long-term financial resilience: firms with low retained earnings (even if positive but close to zero) exhibit significantly higher default probability, even absent excessive leverage or particularly risky sector exposure.

M&A implication: Due diligence must prioritize historical earnings generation and retention policies. A target with low retained earnings—even in a stable sector—warrants deep scrutiny of dividend policy and past profitability trajectory.

2. Fiscal Year (fyear): Persistent Business Cycle Effect

Fiscal year ranks second, capturing macroeconomic cycle effects across 2000–2018 (2008–2009 financial crisis, post-2010 expansion). Even with strong accumulated resilience, a firm becomes vulnerable when operating in an adverse cycle phase.

3. EBIT: Core Operating Profitability Signal

EBIT ranks third, confirming that current operating profitability remains a key indicator of management quality and competitive positioning. Its predictive power, however, is modulated by accumulated resilience and macro-sectoral context.

4. Macro-Sector Classification (Division): Sector Exposure Structures Risk

Certain industries are structurally riskier regardless of individual firm management quality. The data confirm this intuition:

High-risk sectors: industries where default looms

Coal Mining: Average probability ~0.55. Highly dependent on commodity prices, which fluctuate with global demand and the energy transition. Strict environmental regulations (emission standards) and high retiree health costs create a toxic mix for bankruptcies, as seen in several US firms between 2010 and 2020.

Local Passenger Transit: Average probability ~0.50. Intense competition from ride-sharing and personal vehicles, thin margins due to fixed costs (fleet maintenance), and demand highly sensitive to crises (e.g., post-COVID collapse). Insufficient public subsidies and fuel inflation drive cascading urban transit bankruptcies.

Water Transport Services: Average probability ~0.45. Weather hazards (storms, floods) disrupt operations; global supply chains expose to cost overruns (unpaid fuel, e.g., Hanjin 2016). Fleet overcapacity and reliance on international trade amplify risks during economic slowdowns.

Oil & Gas Extraction: Average probability ~0.40. Extreme dependence on volatile oil prices driven by geopolitics and energy transition. Operational risks (accidents, exploration costs) and high infrastructure debt frequently lead to restructurings, as seen in the 2020 price crash.

Textile Mill Products: Average probability ~0.35. Fierce global competition (low-cost Asia), volatile raw material supply chains (cotton), and growing sustainability pressures (e.g., Renewcell bankruptcy in 2024 due to high recycling costs). Fashion demand swings and raw material inflation trigger failures.

Resilient sectors: industries with stronger crisis resistance

Nondepository Credit Institutions: Average probability ~0.20. High resilience due to strict federal regulation limiting excessive exposures and adaptability to cycles via alternative lending products. Less affected by traditional banking crises, they benefit from supportive monetary policy.

Leather Products: Average probability ~0.18. Sustainability innovation (eco-friendly finishes) and localized supply chains reduce vulnerabilities. Niche demand (luxury, craftsmanship) and quality-focused regulations limit bankruptcies despite international competition.

Railroad Transportation: Average probability ~0.15. Heavily subsidized infrastructure (e.g., $23 billion annually in the US) and 1980 deregulation boosting efficiency. Essential freight logistics ensure resilience against shocks, unlike more volatile modes.

.

Legal Services: Average probability ~0.12. Steady or even increased demand during recessions (insolvencies, restructurings, litigation). High entry barriers (professional qualifications) and rapid adaptation to crises (boom in insolvency practices during downturns) provide strong stability.

Fishing & Hunting: Average probability ~0.10. Stable regulation (quotas, Chapter 12 aid for farmers/fishers), manageable seasonality, and local niches. Despite environmental risks, subsidies and constant food demand strongly limit mass failures.

The model highlights how price volatility and public support influence bankruptcy risk.

Implication for target screening: Before analyzing financial statements, macro-sectoral exposure must be qualified. A high-EBIT target in a structurally declining sector carries higher risk than a moderate-EBIT target in a resilient sector.

3. Financial Indicators Conditioned by Resilience and Context

Long-term debt, EBIT, EBITDA, net sales, and current assets rank in the top 10 SHAP values, but only after accumulated resilience, business cycle, and macro-sector exposure. These indicators remain important, but their predictive power is strongly modulated by historical retained earnings and the broader macro-sector environment.

Implications for M&A Practice

1. Due Diligence: Prioritize Assessment of Accumulated Resilience and Macro-Sector Exposure

The findings suggest a revised analysis sequence:

Step 1 – Accumulated resilience assessment: review of retained earnings history and dividend policy.

Step 2 – Macro-sector qualification: identification of cyclical exposure and sector positioning.

Step 3 – Conditional financial analysis: interpretation of ratios in light of resilience, cycle, and macro-sector context.

2. Valuation: Incorporate Resilience and Macro-Sector Exposure into WACC

A target with low retained earnings or high macro-sector exposure should carry an elevated discount rate (WACC) – even with solid operating ratios – reflecting heightened structural vulnerability to external shocks.

3. Transaction Structuring

When SHAP analysis reveals significant macro-sector exposure, protective mechanisms should be strengthened:

Price adjustment clauses: final price indexed to macro-sector indicators (sector index, GDP growth, commodity prices).

Conditional earn-out: deferred payment tied to performance, adjusted for macro-sector effects (EBITDA normalization vs. sector average).

Warranties & indemnities: strengthened guarantees on macro-sector assumptions underlying the business plan.

Model Performance: Random Forest Leads

On the test set, discriminative performance (AUC-ROC) is as follows:

Random Forest: AUC = 0.86 | High robustness, native SHAP interpretability.

LightGBM: AUC ≈ 0.81 | Lower performance in this setup.

Neural networks: AUC = 0.80 | Comparable performance but higher complexity and lower interpretability.

Clustering + rules: AUC = 0.79 | Useful descriptive segmentation, but weaker predictive power.

Methodological Limitations and Enrichment Perspectives

Methodological Limitations

Temporal scope: Dataset ends in 2018, before COVID-19, post-2021 inflation, recent geopolitical tensions, and accelerated energy transition. Macro-sector patterns have since evolved.

Geographic scope: Nasdaq and NYSE only. Risk dynamics differ significantly in Europe (different regulation, financing structures), Asia, or emerging markets.

Missing variables: Critical qualitative factors not captured in structured financials: management quality, governance, ongoing litigation, ESG exposure, patents & R&D, client-supplier concentration.

Enrichment Perspectives

Alternative data: Integration of textual data (NLP on annual reports, earnings call transcripts, sector press) to capture market sentiment and early deterioration signals.

ESG data: ESG scores emerge as resilience predictors (strong governance, climate risk management). Their inclusion would improve predictions in transition sectors (energy, automotive).

Dynamic models: Forecasting risk trajectories (temporal score evolution) rather than annual snapshots – especially useful for anticipating gradual deteriorations.

Sector specialization: Training division-specific models to capture industry-specific logics (e.g., airline risk heavily depends on jet fuel prices and passenger traffic – variables absent from the generic model).

Conclusion: Toward Explainable AI-Augmented Due Diligence

This empirical study of 80,000 observations demonstrates that, within this scope, accumulated financial resilience (via retained earnings), cyclical positioning (fyear), and macro-sector exposure (division) are the primary determinants of corporate default risk, ahead of most operational financial indicators. This finding challenges traditional approaches that often prioritize profitability and leverage ratios first.

For M&A and private equity transactions, the strategic implication is clear: assessment of long-term earnings retention capacity and macro-sector positioning must precede detailed financial ratio analysis.

SHAP-based explainability turns probabilistic predictions into actionable insights, enhancing decision-maker confidence and regulatory compliance in complex, regulated environments.

Explainable AI does not replace business expertise: it enhances it. It quantifies intuition, reveals patterns invisible to the naked eye, and provides a rigorous framework for decision-making in demanding, regulated contexts.

This project is the antithesis of a black box. Source code is publicly available on GitHub.

About LJ Advisory

M&A and corporate finance advisory firm specializing in target search, cross-border due diligence, business valuation, and transactions. Over 20 years of expertise serving private equity funds, strategic acquirers, and financial institutions.